Inez McCormack (1943-2013) was a Irish trade union leader and human rights activist. Born Inez Murphy into an Ulster Protestant family in Cultra, County Down, she once recalled; “recalled: “I was a puzzled young Prod – until I was 17 I hadn’t knowingly met a Catholic. I was a young Protestant girl who didn’t understand that there were grave issues of inequality, injustice and division in our society.”

Author: Charlie Lord

Calls To Distant Places – By Peter Jordan

“Calls To Distant Places” is set in Belfast, Ireland. Peter Jordan is an Irish short story writer who spends his time between Belfast & Donegal. His latest collection of short stories, also titled “Calls To Distant Places” was recently published in Ireland. He has won the Bare Fiction prize, placed second in the Fish, and was shortlisted for the both the Bridport & Bath Short Fiction and Flash Fiction prizes.

Peter has kindly agreed to share another story with our American readers to help us all get through the Coronavirus lockdown. Please leave your thoughts in the comment section below. Enjoy.

Calls To Distant Places

It was two in the morning. When I got out of the taxi I saw my neighbor Joe across

the street standing at his front gate. I hadn’t spoken to him in months. His wife had

cancer and my wife had just had a baby.

– Hi Joe, I said.

He motioned to me.

– What’s up? I said.

– It’s Bruno.

Bruno was Joe’s Golden Retriever.

– I came downstairs for a cigarette, it must have been his heart, he’s been on

medication.

I didn’t know what to say.

– I need to get him in the boot of the car. I don’t want Grace to see him. She’s

been through enough already.

We walked together up the slope of the driveway to the house. He opened the

car boot and lifted out his fishing gear. There was a chill and I could see my own

breath.

Joe came out of the garage with black bin liners and arranged them carefully

along the bottom of the boot. When he had finished, I followed him into the house. I

hadn’t been in the house since last summer. When we walked inside, I could smell

synthetic air freshener.

In the living room, the dog was lying on a throw on the sofa.

Joe had really let the place go: on one of the seats, beside the television, was

a pile of old magazines and newspapers. There were ashes and white tissues in the

grate and on the hearth.

Joe got on his knees and cradled Bruno’s head and I tried to lift his hind legs.

He was still warm. Then Joe said: Wait. And he placed the throw over him, and we

lifted him off the sofa in that manner. We carried him carefully through each doorway

to the outside and placed him in the boot of the car. Then Joe bent down and kissed

him on the forehead before finally closing the boot. I patted Joe on the shoulder and

we both went back inside.

In the kitchen he reached up above the grill, opened a cupboard and took out

a bottle of Jameson.

Then he nodded towards the sink. Help yourself to a glass, he said.

As I walked towards the sink, I kicked a bowl of dried dog food. It was half

empty. And I cursed.

– Sorry about the mess, said Joe.

I lifted a glass and rinsed it under the hot tap, running my fingers inside and

along the rim to clean it.

I’d been drinking beer all night and I wasn’t ready for the whiskey. It tasted

earthy. It would take a bit of getting used to. I patted my pockets for my cigarettes,

stood up and offered one to Joe.

– I’m just going to check on Grace, he said. I’m not smoking in the house

anymore.

I heard his weight on the stairs as I patted every pocket for my lighter. When I

found it, I stepped outside on to the patio. The intruder light came on immediately.

I remembered last summer. We had only just moved in. Joe had called at the

door to introduce himself. He had caught two sea trout: a cock and a hen. The male

fish was around four pounds, the female a pound lighter.

He brought me over a generous cut from each fish. My wife, Anna, said she

couldn’t eat them after having just seen them whole. I wrapped them in tinfoil and

cooked them in the oven with just a little olive oil, salt and pepper. They didn’t taste

like farmed fish. These fish, you could taste the river in them.

Anna said we should invite Joe and Grace over for a drink. They both came

over with wine and beer. And, when the sun moved behind our house, we all carried

our drinks across the street to Joe and Grace’s. I remembered Grace carrying her

sandals in one hand and a wine glass in the other.

They were both older than us by twenty years but there was a bond. Grace

really hit it off with Anna. I think in many ways they were very similar — they had a

lot in common.

Joe had said he would take me fly-fishing He gave me a cork-handled

beginner’s rod, showed me how to cast. I had been practicing with that rod; casting

from my patio until I could land the fly on my compost bin. The fishing season had

come and gone — I’d paid £120 for a fishing license — and I hadn’t got to fish.

Joe stepped outside. The intruder light came back on.

– She’s sleeping, he said.

I offered him a cigarette and he accepted. Stood there in a white short-

sleeved shirt he didn’t seem to notice the cold.

– How’s Anna?

– She’s good, I said. Anna’s good.

– And the baby?

– The baby’s good.

– A good sleeper?

I nodded. The truth is I was sleeping in the spare room. I felt like Anna and I

were drifting apart since the baby had come along.

– My son left before you moved in, said Joe. He’s an accountant, lives in

Australia now.

He drained the glass.

– I might visit when things settle down here.

He went back inside for the bottle and, when he came back outside, he asked:

Have you changed a nappy yet?

– Not yet, I said.

– I never changed a single nappy. Grace did it all.

Then he drained the glass, looked up at the sky.

– It’s my turn now, he said.

I lifted the glass, but I didn’t drink from it.

– Joe, I said. I gotta go.

I offered him my hand. He shook it.

– Tell Anna I said hello, he said, and say hi to the baby.

Then he walked me through the house. On the front porch he hugged me, and

he didn’t let go.

– I’m sorry about the fishing, he said.

Who Won the Donkey Derby? A short story by Irish writer Peter Jordan.

“Who Won the Donkey Derby?” by Peter Jordan. Peter is an Irish short story writer who spends his time between Belfast & Donegal. His latest collection of short stories titled “Calls To Distant Places” was recently published in Ireland. He has won the Bare Fiction prize, placed second in the Fish, and was shortlisted for the both the Bridport & Bath Short Fiction and Flash Fiction prizes.

He has kindly agreed to share a tale with readers in the US to help us all get through the Coronavirus lockdown. “Who Won the Donkey Derby” is set in Donegal in Ireland’s north west. Leave your review in the comment section below. Enjoy.

Who won the Donkey Derby?

I open the door of the bar and stop momentarily to allow my eyes to adjust to the change in light. There are only two small windows, and they’re low set, so that even early in the day it’s dim inside.

Biddy Barr, the owner, sits behind the counter on a stool. The bar was once the living room and back room of her family house.

There’s only one other punter. He sits on a stool at the far end of the counter; his back to the television and the fire, with two pints of Smithwick’s in front of him.

It’s early. Already, he looks drunk.

– Who won the Donkey Derby? he says, to no one in particular.

The small red tractor outside, with the hand-painted number plate and the cushion inside the plastic Centra carrier bag on the seat, is his.

His name’s Magill, Ger Magill.

He drives that small red tractor into town like you’d take your car, and he owns farmland up at Quigley’s Point. But he doesn’t farm the land — something happened to him when he was a child. He drinks.

Biddy gets up off her stool.

– A pint of Heineken, is it?

– Yes, please.

I lean forward and watch her pouring. As I lean over the counter, I can see into the kitchen. It’s like the kitchen of any house in the town. There’s a combined food and water bowl for her cat on the linoleum floor.

– Who won the Donkey Derby? says Ger Magill.

– What’s it like out? asks Biddy.

I have to think. I look down at the counter.

– It’s dry, I say, finally.

She raises her chin.

– That’s a blessing.

Biddy isn’t one for conversation. She isn’t one for anything really, but there are no snide remarks if you suddenly show up after months spent drinking up the town.

I take a gulp of Heineken and pull a face.

– Do ya want a wee splash of lemonade?

I blow out. And nod.

Biddy unscrews the lid on a glass bottle of brown lemonade that sits in amongst the other glass bottles of cordial on a circular tray. And she pours a splash of brown lemonade into what remains of the white head of the Heineken.

It goes down a bit easier with the hint of lemonade. I finish it quickly. Then I let out a sigh.

Biddy takes the empty glass from my hand and angles it under the pump. With Biddy you only have to tip your empty glass forward and she’ll rise from her stool, take the glass from your hand, and refill it.

– Who won the Donkey Derby? says Ger Magill.

I stare in his direction, then at the television behind him, but I can’t decipher a thing.

When Biddy sets the second pint in front of me it looks much better than the first.

– D’ya want another wee splash of lemonade?

– No thanks, I’ll just go with it.

– Right you are.

This one goes down easier.

When I’m on my third pint, Ger Magill gets up off his stool and walks slowly, in a stoop, from the far end of the bar to where I’m sitting.

He looks directly at me.

– D’ya hear me… who won the Donkey Derby?

I don’t know the man. I mean, I know of him. I know his father was a drunk, and a mean bastard. And I’ve been stuck behind that red tractor often enough.

– I don’t know, I say. Who won the Donkey Derby?

He stabs his thumb into his chest.

– Me! he says.

Who are the Scots-Irish? A Beginners Guide.

I nearly called this blog post “Who were the Scots-Irish?” But “were” is past tense, and the Scots-Irish of America are not a historical footnote, they live and breathe here in the United States today. The problem is, many are simply not aware of their Scots-Irish roots.

Scottish Lowland Roots:

The Scots-Irish began their journey to America from the Lowlands of Scotland. The Scottish Lowlands is an area from the Clyde in the East across to the Firth of Forth in the West, and everything south, all the way to the English border. The Scots-Irish are primarily, but not exclusively, Presbyterian. They first arrived in Ulster (in the Northern part of Ireland) in 1604. They lived in Ireland for approximately 100 years before the beginning of the Great Migration to the American Colonies in 1718. That is not to say all the Scots-Irish migrated “en masse” to North America. To the contrary there are approximately 800,000 Protestants still resident in Ulster, many of whom are Scots-Irish Presbyterians, while others are of English, Welsh or even French Huguenot heritage. At this point I would like to note that the Scots-Irish living in Ulster today use the term “Ulster-Scots” rather than Scots-Irish. As the term Scots-Irish is used exclusively in America, and as we are in the United States, I will use the term Scots-Irish in this blog.

There were three waves of Scottish migration to Ireland in the early part of the 17th Century. The first Scottish settlement came in 1604 to 1605. Influential Irish landowner Randal MacDonnell, in a deal with King James 6th of Scotland (who also became King James the 1st of England), was granted extensive additional land in North Antrim. This land grant of “The Route” was agreed providing Randal MacDonnell settled the new lands with Scottish Protestants. An agreement was made which may have increased MacDonnell’s holdings in the area up to 300,000 acres. This deal was unusual at the time as Randall MacDonnell was a Catholic, there was even a chapel in his residence at Dunluce Castle. However, MacDonnell acquired the land and therefore more wealth, while James (now King of both Scotland and England) increased the Protestant population of Ulster, Protestants being considered more loyal to the crown than the native Irish. So both these powerful men were happy with the arrangement and the ensuing plantation.

The 2nd wave came came in 1606 with Hugh Montgomery and James Hamilton. This was a private undertaking by these two prominent Scottish Landowners, whereby they acquired two thirds of the land of native Irish Chieftan Conn O’Neill. This acquisition seems a little opportunistic, if not downright deceitful. But more on this little piece of intrigue in another post. Having acquired the land of Conn O’Neill, Montgomery and Hamilton sent over tenants from their estates in the Scottish Lowlands, places such as Dumfries & Galloway & Ayrshire. They settled primarily the North Down area of Ireland, areas such as Comber, Bangor, Donaghadee, Newtownards and further along the Ards Peninsula. It is thought between 1604 to 1607 around 10,000 Scots migrated to Ulster as part of the MacDonnell, Montgomery & Hamilton enterprises. It is thought the success of these first two plantations influenced King James in his subsequent decision to grant the Charter for the 1607 Jamestown Settlement in Virginia.

Thirdly came the official plantation. King James was enthused by the success of the two previous enterprises, but in 1607 a major event also took place, the Flight of the Earls. This happened in Sept 1607 when the Irish nobility fled from Rathmullan on Lough Foyle to Continental Europe in an attempt to evade persecution, and rally Catholic support for their cause. By 1608 King James of England took the opportunity to seize the large landholdings of these native Irish Cheiftans and settle them with Protestant subjects. The official Plantation of Ulster had begun. Initially King James wanted the Plantation to be available to both English & Scottish Protestant subjects, but for a variety of reasons the Scottish Presbyterians were the great majority of settlers.

The Scots-Irish remained in Ireland for generations, approximately 100 years. They made a living from farming and trading in the growing towns such as Derry / Londonderry and Belfast. They lived through the Irish rising of 1641, the Siege of Derry in 1689 and the Battles of the Boyne, Aughrim and Limerick from 1690 to 1691. They brought with them to Ireland many Scottish customs, speech patterns, architecture etc. But they also adopted many Irish traits during their long soujourn in the Emerald Isle. By 1718 they began to migrate to the New World.

This migration began in earnest in 1718. The Scots-Irish who came to America were almost entirely Presbyterian. At the time in Ireland they were considered “Dissenters”. This meant they were not congregants of the Established Church of England (in Ireland known as the Church of Ireland), with the English monarch as head. Also, because of their “dissenter” status, some of the harsh Penal Laws designed primarily for the native Irish Catholics also applied to the Presbyterians. For example, the Penal Laws meant the Scots-Irish could not be elected to public office & therefore could not effect the laws by which they were governed. They also had to pay “tithes” (taxes) to the Established Church even though they did not worship there. These “tithes” would have been used to pay for the upkeep of the Established Church and not their own Presbyterian churches & preachers. Both the Presbyterians and the Catholics greatly resented this law. In addition, economic circumstances caused rents to rise rapidly during this period while incomes fell. Here I examine in more depth these reasons “Why the Scots-Irish Came to America”. But for now, suffice to say, between 1718 and 1770 there took place a Great Migration of Scots-Irish to the American Colonies. On the eve of the American Revolution in 1775, more than 250,000 Scots-Irish called the New World home. It is said that “one in six” of the Colonists were Scots-Irish.

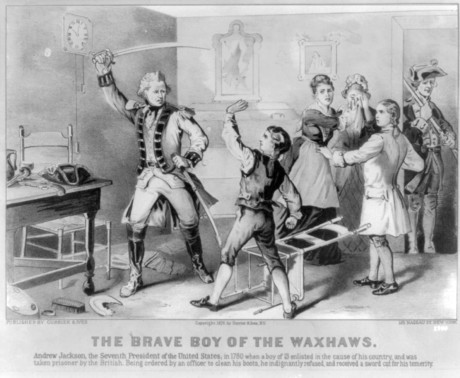

Their significant role in the ensuing American Revolution cannot be overstated. Indeed, King George of England referred to it as the American Revolution as the “Presbyterian Rebellion”. The Scots-Irish experience at the hands of the English in Ireland was fresh in their minds, stories handed down from father to sons and daughters. By way of example, President Andrew Jackson’s parents had a farm just outside Carrickfergus in Ulster. They were both born in Ireland as was Jackson’s older brother. The family sailed for America around 1765. Their home life in the U.S. would have been a Scots-Irish existence. The music, food, farming techniques, construction techniques, dance, speech patterns, bible teachings etc would all have been heavily informed by their lives in Ireland. Andrew Jackson and his two older brothers all fought in the American Revolution. This life experience was replicated in Scots-Irish regions throughout the nation. Taxation without representation was not going to wash in the New World; the Scots-Irish were angry and would fight for their rights.

Charles Lord. M.Ed

Celtic 1 – 0 Sevco

What a team goal this was! 🤩

📹 #CelticTV's unique angle of yesterday's #CELRAN winner…

@OlivierNtcham 🔛🔥 pic.twitter.com/zhAeghAFs3— Celtic TV (@CelticTV) September 3, 2018

10% OFF Everything – Use Coupon Code: IRELAND

Irish American Influence in USA – Info Graphic

The influence of 34.6 million Irish-Americans is felt everyday through every aspect of American life and culture. “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”. JFK. Happy St.Patrick’s Day to all our wonderful customers; could not do it without you.

Related articles across the web

Irish Tweed Caps – Traditional Craft meets Modern Fashion

History of the Irish Tweed Flat Cap – A Traditional Craft:

Irish Tweed Caps get their distinctive colors and patterns from the landscape of Ireland. It is the beauty and quality of the fabric that makes the Irish Tweed Caps so special, and so sought after internationally. The colors match the patterns seen from the cottage window: of turf and hill and fuschia, of sea and cloud and sky.

Anyone who has spent time in Ireland will know just how changeable the climate can be. Four seasons in one day are not uncommon, even in midsummer. Tweed Flat caps became the perfect headwear for those working outdoors,

trapping warmth head and waterproofing the wearer.

The customary process of making it is unlike any other, resulting in a signature color-flecked weave. Woven from woolen spun yarns, it is characterized by its plain weave structure composed of uneven slub yarns contrasting with the ground color. Traditionally, the woman of the house spun the yarn from the family sheep’s wool and the husband then weaved the spun wool. The original patterns were a black and white herringbone when the colors were limited to the colors of the sheep’s wool. With blackface sheep, the weaver used whatever mixture they could make from that to make a black and white or grey and white pattern. And it is these colors, and the individual colored flecks, that give Irish Tweed Caps their characteristic classic design.

The customary process of making it is unlike any other, resulting in a signature color-flecked weave. Woven from woolen spun yarns, it is characterized by its plain weave structure composed of uneven slub yarns contrasting with the ground color. Traditionally, the woman of the house spun the yarn from the family sheep’s wool and the husband then weaved the spun wool. The original patterns were a black and white herringbone when the colors were limited to the colors of the sheep’s wool. With blackface sheep, the weaver used whatever mixture they could make from that to make a black and white or grey and white pattern. And it is these colors, and the individual colored flecks, that give Irish Tweed Caps their characteristic classic design.

With the introduction of dyes the tweed took on a range of new and very distinctive colors. Children would gather the colors locally from the Irish landscape to dye the wool: purple blackberries, orange lichen, yellow gorse and the plentiful red fuschia that is such a  distinctive summer feature of the Donegal countryside. The dyes were brewed by heating the plants and lichens in a large cooking pot on the household turf fire. This was then allowed to cool before the pure new wool from the household sheep was steeped.

distinctive summer feature of the Donegal countryside. The dyes were brewed by heating the plants and lichens in a large cooking pot on the household turf fire. This was then allowed to cool before the pure new wool from the household sheep was steeped.

Come October, the farmers would come in from the fields to stretch the white yarn the length of the loom frame – known as warping the loom. Then fine-tune the shuttle that would weave a contrasting vertical yarn – the weft – across the warp.

Traditional wooden handlooms differ only slightly in design and operation from those used in biblical times. The loom is operated manually and the weaving may be described as passing the horizontal threads – the weft – through the warp by means of a shuttle. Thread by thread and row by row, the weft is eased into place. The complicated permutations of color and design are coordinated and interpreted as the weaver proceeds.

The warp is the first step in arranging the various colors to form a foundation upon which the weaver will, with almost magical skill, produce the pattern. It can take even the best weavers up to half a day to draw 1000 threads through the reed to form the warp to the age-old pattern. However, a good weaver – seated at a bench attached to a wood loom, coordinating hand and foot movements – could produce up to thirty yards of fabric a day.

magical skill, produce the pattern. It can take even the best weavers up to half a day to draw 1000 threads through the reed to form the warp to the age-old pattern. However, a good weaver – seated at a bench attached to a wood loom, coordinating hand and foot movements – could produce up to thirty yards of fabric a day.

Hand-weaving is a skill that has been passed down through generations. Many families lived by both the hand-spinning and hand-weaving of cloth in their homes, then selling their unique family product at the local tweed market.

In many parts of Ireland hand-weaving is still practiced in the very same way as it was over 200 years ago. In Donegal it is a hereditary skill that has passed from generation to generation over many centuries. It is one of the few survivors of the ancient craft, which now serves the modern world. The tradition of making Irish Tweed Flat Caps is still carried on today by the Hanna family of Donegal Town who are world renowned for the quality of the Hanna Hats Irish Tweed Flat Caps.

Contributed by Joe Summer

Women of Easter Week 1916.

The following, in her own words, are the recollections of Moira Regan who was in the GPO, Dublin, during Easter Week 1916. A member of Cumann na mBan she was one of the Women of Easter Week 1916.

“At 6 o’clock on the evening of Easter Monday I went down O’Connell Street to the Post Office,” she said. “But that was not my real entrance into the affairs of the uprising. You see, I belonged to an organization called Cumann na Mban—the Council of Women. We had been mobilized at noon on Monday near the Broad Stone Station, being told that we’d be needed for bandaging and other Red Cross work.

“But late in the afternoon we got word from the Commandant that we might disperse, since there would not be any street fighting that day, and so our services would not be needed. The place where we were mobilized is three or four blocks from the Post Office, and we could hear the shooting clearly. There were various rumors about—we were told that the Castle had been taken, and Student’s Green and other points of vantage. And at last, as I said, we were told that there would be no street fighting, and that we were to go away from the Broad Stone Station and do what good we could.

“When I got to the Post Office that evening I found that the windows were barricaded with bags of sand, and at each of them were two men with rifles. The front office had been made the headquarters of the staff, and there I saw James Connolly, who was in charge of the Dublin division; Padraic Pearse, Willie Pearse, O’Rahilly, Plunkett, Shane MacDiarmid [Seán Mac Diarmada], Tom Clarke, and others sitting at tables writing out orders and receiving messengers.

“On my way to the Post Office I met a friend of mine who was carrying a message. He asked me had I been inside, and when I told him I had not, he got James Connolly to let me in.

“I didn’t stay at the Post Office then, but made arrangements to return later. From the Post Office I went to Stephen’s Green. The Republican army held the square. The men were busy making barricades and commandeering motor cars. They got a good many cars from British officers coming in from the Fairy House races.

“The Republican army had taken possession of a great many of the public houses. This fact was made much of by the English, who spread broadcast the report that the rebels had taken possession of all the drinking places in Dublin and were lying about the streets dead drunk. As a matter of fact, the rebels did no drinking at all. They took possession of the public houses because in Dublin these usually are large buildings in commanding positions at the corners of the streets. Therefore the public houses were places of strategic importance, especially desirable as forts.

“That night there was not much sleeping done at our house or at any other house in Dublin, I suppose. All night long we could hear the rifles cracking—scattered shots for the most part, and now and then a regular fusillade.

“On Tuesday I went again to the Post Office to find out where certain people, including my brother, should go in order to join up with the Republican forces. I found things quiet at headquarters, little going on except the regular executive work. Tuesday afternoon my brother took up his position in the Post Office, and my sister and I went there, too, and were set at work in the kitchen. There we found about ten English soldiers at work—that is, they wore the English uniform, but they were Irishmen. They did not seem at all sorry that they had been captured, and peeled potatoes and washed dishes uncomplainingly. The officers were imprisoned in another room.

“The rebels had captured many important buildings. They had possession of several big houses on O’Connell Street near the Post Office. They had taken the Imperial Hotel, which belongs to Murphy, Dublin’s great capitalist, and had turned it into a hospital. We found the kitchen well supplied with food. We made big sandwiches of beef and cheese, and portioned out milk and beef tea. There were enough provisions to last for three weeks.

“About fifteen girls were at work in the kitchen. Some of them were members of the Cumann na Mban, and others were relatives or friends of the Republican army which James Connolly commanded. Some of the girls were not more than sixteen years old.

“We worked nearly all Tuesday night, getting perhaps an hour’s sleep on mattresses on the floor. The men were shooting from the windows of the Post Office, and the soldiers were shooting at us, but not one of our men was injured. We expected that the Inniskillings would move on Dublin from the north, but no attack was made that night.

“On Wednesday I was sent out on an errand to the north side of the city. O’Rahilly was in charge of the prisoners, and he was very eager that the letters of the prisoners should be taken to their families. He gave me the letter of one of the English officers to take to his wife, who lived out beyond Drumcondra. It was a good long walk, and I can tell you that I blessed that English officer and his wife before I delivered that letter!

“As I went on my way, I noticed a great crowd of English soldiers marching down on the Post Office from the north. The first of them were only two blocks away from the Post Office, and the soldiers extended as far north as we went—that is, as far as Drumcondra. But nobody interfered with us—all those days the people walked freely around the streets of Dublin without being interfered with.

“As we walked back, we saw that the British troops were setting up machine guns near the Post Office. We heard the cracking of rifles and other sounds which indicated that a real siege was beginning. At Henry Street, near the Post Office, we were warned not to cross over, because a gunboat on the river was shelling Kelly’s house—a big place at the corner of the quay. So we turned back and stayed that night with friends on the north side of the town. Our home was on the south side.

“There was heavy firing all night. The firing was especially severe at the Four Courts and down near Ring’s End [Ringsend] and Fairview. The streets were crowded with British soldiers; a whole division landed from Kingstown.

“That was Wednesday night. On Thursday we thought we’d have another try at the Post Office. By devious ways we succeeded, after a long time, in reaching it and getting in. We found the men in splendid form, and everything seemed to be going well. But the rebels were already hopelessly outnumbered. The Sherwood Foresters had begun to arrive Tuesday night, and on Wednesday and Thursday other regiments came to reinforce them. Now, a division in the British Army consists of 25,000 men, so you can see that the British were taking the rising seriously enough.

“The British soldiers brought with them all their equipment as if they were prepared for a long war. They had field guns and field kitchens, and everything else. Most of them came in by Boland’s Mills, where de Valera was in command. They suffered several reverses, and many of them were shot down.

“The chief aim of the British was, first of all, to cut off the Post Office. So on Thursday messengers came to Pearse and Connolly, reporting that the machine guns and other equipment were being trained on the Post Office. But the men were quite ready for this and were exceedingly cheerful. Indeed, the Post Office was the one place in Dublin that week where no one could help feeling cheerful. I didn’t stay there long on Thursday morning, as I was sent out to take some messages to the south side. I had my own trouble getting through the ranks of soldiers surrounding the Post Office, and when I eventually delivered my messages I could not get back. The Post Office was now completely cut off.

“Thursday evening, Friday, and Saturday I heard many wild rumors, one insistent report being that the Post Office was burned down. As a matter of fact, the Post Office was set on fire Friday morning by means of an incendiary bomb which landed on top of the door. All the other houses held by the rebels had been burned to the ground, and the people who had been in them had gone to the Post Office, where there were now at least 400 men.

“The Post Office burned all day Friday, and late in the afternoon it was decided that it must be abandoned. First Father Flanagan, who had been there all the time, and the girls and a British officer—a Surgeon Lieutenant, who had been doing Red Cross work, were sent to Jervis Street Hospital through an underground passage. Then all the able-bodied men and James Connolly (who had broken his shin) tried to force their way out of the Post Office, to get to Four Courts, where the rebels were still holding out. They made three charges. In the first charge O’Rahilly was killed. In the second many of the men were wounded. In the third the rebels succeeded in reaching a house in Moor Lane [Moore Street] back of the Post Office. There they stayed all night. They had only a little food and their ammunition was almost exhausted. So on Saturday they saw that further resistance was useless, and that they ought to surrender, in order to prevent further slaughter.

“There were three girls with the men. They had chosen to attend Commandant Connolly when the other girls were sent away. One was now sent out with a white flag to parley with the British officers. At first she received nothing but insults, but eventually she was taken to Tom Clarke’s shop, where the Brigadier General was stationed. Tom Clarke was a great rebel leader, one of the headquarters staff, so it was one of the ironies of fate that the General conducted his negotiations for the surrender of the rebels in his shop.

“Well, the Brigadier General told this girl to bring Padraic Pearse to him. Pearse came to him in Clarke’s shop and surrendered. Pearse made the remark that he did not suppose it would be necessary for all his men to come and surrender.

“‘But how,’ said the General, ‘can I be sure that all your men will lay down their arms?’

“‘I will send an order to then,’ said Pearse. And he called to him Miss Farrell, the girl who had been sent to the General, and asked her would she take his message to his men. She said she would, and so she took the note that he gave her to the rebel soldiers that were left alive, and they laid down their arms.

“There are a few things,” said Moria Regan, “that I’d like everyone in America to know about this rising, and about the way in which the British officers and soldiers acted. When the rebels surrendered they were at first treated with great courtesy. The British officers complimented them on the bold stand they had made, and said they wished they had men like them in the British Army. But after they had surrendered they were treated in the worst possible way. They were cursed and insulted, marched to the Rotunda Gardens, and made to spend the night there in the wet grass. They were not given a morsel of food.

“The man chiefly picked out for insult was Tom Clarke. He was very shamefully treated—it was a great contrast to the way in which the British officers spoke to him at the time of his surrender.

The GPO after the Rising. This photo accompanied the original article.

“The next morning the prisoners were marched to Richmond Barracks on the other side of the city from the Rotunda. One of the prisoners, Sean MacDiarmuid [Mac Diarmada], was very lame, but was obliged to march with the rest. And on the way the crowds of English soldiers in the streets kept shouting, ‘Shoot the dogs! What’s the use of taking them any further?’

“Now, all the headquarters staff had surrendered. Notice was sent around that a truce had been arranged. The priests had arranged this. Miss Farrell was sent around in a motor car with Pearse’s note calling on all the rebels to surrender. Now, most of the fighting stopped, except for sniping from the roofs, and for some heavy fighting at Ring’s End [Ringsend], which continued for two days.

“The treatment of the prisoners in the jails was horrible. Many of the men arrested were not at all in sympathy with the Sinn Fein movement. The British arrested every one who had advocated the restoration of the Irish language, or had lectured on Irish literature, or had worked for the cause of Irish manufactures—they arrested every one, indeed, who had been conspicuously associated with anything definitely Irish.

“In one small room eighty-four prisoners were kept for two weeks. For two days they were not permitted to leave the room at all for any purpose. For thirty-seven hours they were without food. Then some dog biscuits were thrown in among them and they were given a bucket of tea. Later they were taken out of the room once a day. All their money was taken from them, but a few of them managed to hide a shilling or so, which they used to buy water of the soldiers.

“After the court-martial they were taken to Kilmainham Jail. There they were put into the criminal cells, without even plank beds. I went to visit one of the leaders, a particular friend of mine, and there was in his cell a blanket and a coverlet—nothing else at all.

“The night before they were to die the prisoners were left to write letters, and some of them were permitted to receive visitors for the first time since their capture. Padraic Pearse was not allowed to see any one. MacDonagh was not allowed to see his wife; he was allowed to see his sister, a nun. The food given them was scanty in quantity and poor in quality. On the morning that he was shot he was given for breakfast a little dry, uncooked cereal, with nothing to put on it.

“The prisoners were shot in the yard of Kilmainham Jail. Then the bodies were taken, in their clothes, outside Dublin to Arbor Hill Barracks and thrown into quicklime in one large trench. In every case the bodies were refused to the relatives of the dead men.

“One thing that would strike you about the conduct of the rebels was the absolute equality of the men and women. The women did first-aid work and cooking, and some of them used their rifles to good advantage. They just did the work that was before them, and they were of the greatest moral aid.

“About eighty women were taken prisoner and thrown into cells in Kilmainham Jail. There were no jail matrons; there was no one in charge of them but soldiers, who took every opportunity to insult them. They were not allowed to leave their cells for any purpose for two days. They were treated just as the men prisoners were treated. The women slept over the yard while the men were shot. They would be awakened in the morning by the sound of the quick march, the brusque command, and the sound of the rifles. One woman imprisoned in Kilmainham Jail was the Countess Plunkett.”

Moira Regan was asked what advantages had come to Ireland as a result of this insurrection.

“Well,” she replied, “for one thing it has shown England that things in Ireland are not all right—that Ireland is not ‘the one bright spot’—that Castle Government in Ireland is a perilous thing. It has made conscription in Ireland impossible. And had it not been for the rising we should have had conscription by now. And Ireland cannot spare any more men. As it is, a great many of the young men of Ireland joined the British Army, being led to do so by Redmond’s urging and by the plea that Ireland should fight for Belgium, and that the small nations of the world should stand together. This was Redmond’s great recruiting argument. I wonder how he reconciles this with the words he used to Asquith the other day in the House of Commons when he said: ‘You betrayed Belgium, now you are betraying Ireland!’

“But the greatest result of the rising, the thing that will justify it even if it were the only good result, is the complete and amazing revival of Irish nationality. We have been asleep—we had been ready to acquiesce in things as they were, to take jobs under the Castle Government and to acquiesce in the unnatural state of affairs. But now we have been awakened to the knowledge that there is a great difference between Ireland and England, that we are really a separate nation. Even the people who were not in sympathy with the rebels feel this now.

“We have been living in a country that had no national life. And suddenly we were shown that we had a national life—that we were a nation, a persecuted and crushed nation, but, nevertheless, a nation.

“You cannot understand the joy of this feeling unless you have lived in a nation whose spirit had been crushed and then suddenly revived. I felt that evening, when I saw the Irish flag floating over the Post Office in O’Connell Street, that this was a thing worth living and dying for. I was absolutely intoxicated and carried away with joy and pride in knowing that I had a nation. This feeling has spread all over Ireland; it has remained and it is growing stronger. We were a province, and now we are a nation; we were British subjects, and now we are Irish. This is what the rising of Easter week has done for Ireland.”

Related articles across the web

Shane Long Goal. Ireland v Germany

So here it is, just in case you wanted to see it again 🙂 Shane Long scores for Ireland against Germany at the Aviva Stadium in Dublin. Ireland later qualified for the Euro’s in France 2016 by beating Bosnia-Herzegovina in the play off. Well done lads. In the words of that great old Irish rebel song “We will march with O’Neill, to an Irish battle field, we will go to fight the forces of the crown”. This time the Irish will be playing to be crowned Kings of European football.

And you heard it here first. Ireland will get out of the group and move onto the last 16. Having been drawn against Italy, Sweden and currently world ranked #1 Belgium, it will not be easy for Ireland. However, Belgium are a collection of great players, but I suspect not a great team. Ireland are the polar opposite, they have no superstars, but they have a terrific work rate and team spirit. With Ireland, the whole is greater than the sum of it’s parts.

Ireland has been drawn against Sweden in the first game and I think the Irish can get a win. Yes, Zlotan Ibrahimovic is excellent, and will be an obvious threat to the Irish defense, but at 34 he is no spring chicken. The Irish work rate and team spirit should carry them through to a win against Sweden. Given the unique nature of international tournaments, with only 4 teams per group, a win in the first game will put Ireland in a terrific position going into the games against Italy and Belgium where draws (ties) should be enough to see Ireland into the next round. O’Neill has already proved Ireland’s approach and tactics will be very different from the overly cautious Irish team under Trapattoni. Having watched Martin O’Neill guide his men through a very tough qualifying group consisting of Poland, Germany, Scotland and Georgia, I am sure he will navigate his team to the last 16 in France. We beat the World Champions Germany, so we can beat anyone. Get in there lads !!!!

Related articles across the web

An Gorta Mor was not an “Irish Famine”.

Thank you to Father Sean McManus of the Irish National Caucus for bringing this article to our attention. Thank you to Michael Nicholson for highlighting the topic in his new book and thank you to the Irish Times for reporting on the issue. An Gorta Mor was not an “Irish Famine”.

Michael Nicholson: “Famine novel changed my mind on England’s guilt.”

Britain’s most decorated reporter set out to write a Famine novel to restore England’s reputation but the facts confounded him. He tells how Trevelyan earned his scorn.

Irish times. Monday, December 14, 2015

Michael Nicholson: Almost all I have written happened in real life. I have exaggerated nothing. There was no need. The truth is  appalling enough and if the reader finds the descriptions of people, events and their outcome hard to believe, then go to the history books and be convinced.

appalling enough and if the reader finds the descriptions of people, events and their outcome hard to believe, then go to the history books and be convinced.

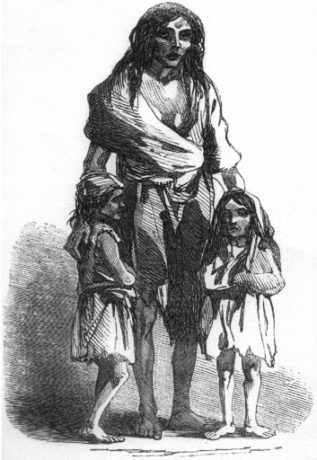

“A million dead. A million fled.” It was those few words that had such an impact on me. Think of it. Try to visualise. Try putting it into a modern context, something happening today, something you are watching on television news, an apocalyptic disaster on an unheard-of scale, something that dwarfs Hiroshima.

A million dying because a foreign blight had turned a potato crop into rotten, stinking, putrefying mush. Try to picture families of living skeletons whispering their last prayer in the shelter of a ditch as they watch others turning black with the fever that spread like a summer fire across bracken from Skibbereen to Donegal, from Wicklow to Clare. Imagine another million, still untouched by it, desperately fleeing their motherland to find safety and sanctuary anywhere and with anyone who would take them. This was Ireland in the Famine years.

As a foreign correspondent for ITN, travelling the globe for more than 30 years, I reckon I have seen more than my fair share of man’s inhumanity to man. It is said that we reporters suffer from an overdose of everything, saturated as we are in the world’s woes. In places like Bangladesh, Sudan, Ethiopia, Rwanda, I became used to dealing in numbers; the dead and dying in their hundreds, or in their thousands, even their tens of thousands. But a million corpses in a forgotten corner of what was then the world’s greatest and wealthiest Empire is inconceivable.

Dark Rosaleen is the story of murder and betrayal, of a starving people held captive, of a failed rebellion and a love that grew out of it during those years of the Great Hunger. In 1845, when the potato crop failed yet again, the British government sent a commissioner to Ireland to oversee the distribution of food aid. In my story his spoilt, overprivileged young daughter Kate is obliged to go with him to what, in her tantrums, she calls “this hateful land of saints and savages”. In her first few months, isolated in her father mansion overlooking Cork, she cares nothing for the suffering outside. Then the scale of the disaster gradually overwhelms her and her selfish arrogance turns to pity and anger. Finally, despairingly, she turns against both her father and her country. She is condemned as a traitor when she joins the rebellious Young Irelanders in their fight to end British rule.

You might think this would have been better written by an Irish author rather than an Englishman. I had a reason. At the start, my intention was to defend the government of Prime Minister Peel, to illustrate the immense physical and political problems trying to feed a starving nation across the Irish Sea. My mindset was that we English had been badly judged, that both England and Scotland were also suffering from the ravages of the blight, that communication between London and Dublin was slow and unreliable, that transporting food aid to the hinterland was a massive problem. In short, I thought there was good reason to reduce England’s blame.

I had read the famine novels of Liam O’Flaherty and Walter Macken, and was moved by their simplicity and pathos. I had listened at length to Ireland’s historical grievances in Dublin and Liverpool, in Cork and in Boston, Massachusetts, wherever Irishmen gathered over a pint of porter or a Jamesons. They spoke of a deliberate policy of imposed starvation, of land clearances, of ethnic cleansing, of exporting Irish peasants in coffin ships that might never reach the far shores of the Atlantic, and all this said as if it was proven historical fact.

Given an Irishman’s well-known considerable verbal licence I was happy to persuade myself that much of it was exaggerated blarney. But as I ploughed even deeper in my research, my characters took over and my storyline went into reverse. It was if I was a prosecuting counsel who had his side changed midway. I was a convert and I ended up with a novel I had not intended to write.

Kate is my heroine and Sir Charles Trevelyan, the government’s director of famine relief, is the villain. This is his real name and all that he does and says in my novel is as they appear, word for word, in the historical records of the time. I make this point because so much of what he said and did is barely believable.

“We will do what is necessary but no more. The Irish peasants are perverse and prefer to beg than borrow. They would rather eat free English food than labour for their own. It would be unjust and unwise to pamper them when our own people are pleading for assistance. I do not intend to transfer famine from one country to another.”

Trevelyan was guided not by any agreed government policy because there was none. He was guided by God. A pious, stubborn, uncompromising, devout evangelist, he saw the blight and the suffering as an act of Providence and to deny it was tantamount to blasphemy. The Anglo-Irish landowners, who considered the Irish peasants vermin, were loud and constant in their support and applause.

Here I must end this historical explainer for fear you will think my novel is yet another academic heavyweight. But against this background is the sequel, the story of Kate and the man who loved her, based on John Mitchel, leader of the rebellious Young Irelanders, the forefathers of Sein Féin. Kate rode with them as they preached their revolutionary gospel, as they attacked the landlords, set fire to their estates, ambushed the Redcoats and stole from the rich to feed the hungry. She became the legendary Dark Rosaleen, named after a banned nationalist poem by James Clarence Mangan.

“The Erne shall run with blood

The earth will rock beneath our tread

And flames wrap hill and wood

And gun-peal and slogan cry wake many a glen serene

Ere you shall fade, ere you should die

My Dark Rosaleen”

In order to turn history into a novel, an author is obliged to dramatise, to put words into mouths that might never have been spoken, to lay blame that perhaps was not entirely deserved. My heroine and her revolutionary lover may not have existed as I portray them. But some part of them will have lived those times and helped forge those times.

Nothing in my pages, not the people nor the lives they lived, is wholly fictional. Almost all I have written happened in real life. I have exaggerated nothing. There was no need. The truth is appalling enough and if the reader finds the descriptions of people, events and their outcome hard to believe, then go to the history books and be convinced.

Michael Nicholson is one of the world’s most decorated journalists, reporting from 18 different war zones over a 45-year career. He was Senior Foreign Correspondent for ITN for ten years, recipient of three Royal Society Journalist of the Year Awards, one BAFTA, the Falkland and Gulf Campaign medals, and an OBE for Services to Television. Dark Rosaleen – a famine novel, is published by The History Press Ireland.

The DUP are unfit for coalition Government.

On Thursday British voters go to the polls to elect their new government. It looks like it is going to be very tight, probably resulting in a hung parliament, with no single party getting an overall majority. Consequently, the right of center British Conservatives

(Tories), are looking around for potential partners to help them form a government. One party they are  considering is the right wing DUP from northern Ireland. But there is a big problem, the DUP have a dubious past and are intolerant right wing evangelicals who are unfit for government in a pluralist democracy.

considering is the right wing DUP from northern Ireland. But there is a big problem, the DUP have a dubious past and are intolerant right wing evangelicals who are unfit for government in a pluralist democracy.

It is well known that since it’s inception the DUP, and their supporters in the Orange Order, have been hostile toward the Catholic community in northern Ireland. The DUP founder, Ian Paisley, was once evicted from the European Parliament after staging an embarrassing protest during which he claimed the Pope was the anti-Christ. And Peter Robinson, the DUP’s current leader, was convicted in an Irish court for participating in a paramilitary incident where pro-British thugs invaded a small Irish village. He was also a member of the infamous Ulster paramilitary group the Third Force, pictured here in paramilitary attire with convicted terrorist Noel Little who traded British missile secrets in return for support and weapons from the apartheid South Africa regime.

Robinson, the DUP’s current leader, was convicted in an Irish court for participating in a paramilitary incident where pro-British thugs invaded a small Irish village. He was also a member of the infamous Ulster paramilitary group the Third Force, pictured here in paramilitary attire with convicted terrorist Noel Little who traded British missile secrets in return for support and weapons from the apartheid South Africa regime.

In recent years the DUP has also begun flexing it’s muscle against the LGBT community in northern Ireland. Examples include the DUP attempting to ban blood donations from gay men, while also opposing gay marriage. The DUP minister for Health at the time, Edwin Poots, wasted considerable amounts of tax payers money pursuing a legal battle over the gay blood ban, a battle he could never win. Some in the DUP ranks recently even expressed a desire to imprison members of the LGBT community; they actually want to criminalize homosexuality. That’s just Dickensian, an approach more suited to Putin’s Russia than a pluralist British democracy. But Peter Robinson has not moved against any in his party that hold such intolerant views. To the contrary, during his tenure, he has elevated “flat earthers” like Edwin Poots and the even more disgraced Jim Wells to cabinet positions. But DUP arrogance does not end there, we cannot overlook the DUP’s treatment of those in northern Ireland who enjoy the Irish language, a practice which is often perceived as a Catholic tradition in the divided streets of Ulster. They are “disrespectful and discourteous” to the parents and children learning the language, and block any act of legislation that would help protect the Irish language in in the North. Yet still no sanction from Peter Robinson against party members such as Gregory Campbell who engage in this prejudiced and embarrassing behavior. Last year the mask slipped and we learned what Peter Robinson and his Pastor McConnell think of Muslims. But recently, through Peter Robinson’s comments on the Abortion bill, we see the rights of women now being trampled on too. Is Peter Robinson’s idea of female equality to let women do his shopping? Does he trust Catholic women and Muslim women to do his shopping?

In proposing “guidelines” as a way forward on the Abortion issue Robinson is either kicking important legislation regarding women’s rights into the ditch, or he is displaying a colossal ignorance about women’s rights issues and how to best address them. But then when you think about it, issues involving marriage and women have not gone well for Peter in the past. He is as useful on these matters as a Catholic priest. It’s a woman’s body, and she should be in charge of it. Not the DUP or the priests. The people of East Belfast should do us all a favor and vote for Niaomi Long. Ms Long is the incumbent MP in the area and is standing against the DUP candidate in the crucial East Belfast constituency. But the DUP in Belfast have been gunning for her for some time. This is the only constituency where electoral defeat may cause the DUP to think again. The people of East Belfast can save us all from the DUP’s fundamentalist hogwash. They make NI look backward in the eyes of the world. The British Conservatives or Labour should not touch the DUP, and their fellow travelers in the Orange Order, with a 30 foot barge pole. If they do they are wide open to accusations of homophobia, anti-Catholic sectarianism, anti-immigrant sentiment etc. The DUP have more in common with the BNP, they are simply not fit for purpose. Many of the DUP leadership are members of the Orange Order, an organization that bans it’s members from marrying Catholics and bans it’s members from even attending a Catholic church. This includes but is not limited to Nelson McCausland, Nigel Dodds, and Gregory Campbell.

A look at their voting patterns should give the British people a further insight into the workings of the DUP. For example, on the gay marriage vote in the northern Irish assembly, not one DUP MLA voted in favor of gay marriage, NOT ONE. The DUP had even lined up a petition of concern should the vote go against them. This is a unique assembly mechanism that means the DUP would have successfully blocked the bill even if it had been passed by a democratic vote. They are fighting gay marriage by any means necessary. The supposedly more moderate UUP entered into an electoral pact with the DUP for this Westminster election, and indeed only one of UUP MLA voted in favour of the bill. In fact, of the 51 DUP / UUP MLA’s, fully 98% voted against the gay marriage bill.

All the while the DUP have been working to bring forward their own anti LGBT conscience clause legislation, which will allow religious fundamentalists to discriminate against the LGBT community. And i’m sure it won’t be long before such legislation could be used liberally against other minorities.

On the other side of the fence, Sinn Fein proposed the gay marriage bill and have long been at the forefront of support for the LGBT community throughout Ireland. The SDLP also supported it, so we can hardly blame the SDLP or Sinn Fein for it’s defeat. Nearly 80% of Alliance MLA’s also supported the bill, two did not. One independent unionist, and two NI21 MLA’s (Basil McCrea + John McAllister) also voted in favour of the bill. Despite this the northern Ireland gay marriage bill was narrowly defeated by the fundamentalist and evangelical DUP.

No pact should be countenanced between British main stream political parties and the DUP. British democracy does not need any political party or associated organization that is anti-women’s rights, anti-gay rights, anti-Catholic or anti-immigrant.

Our DUP friends would do well to remember the old Belfast adage, “Jesus Saves, but Georgie Best scored the rebound.”