Symbolism is no substitute for constitutional generosity

Today the Commonwealth consists of 56 member states, 36 of them are Republics.

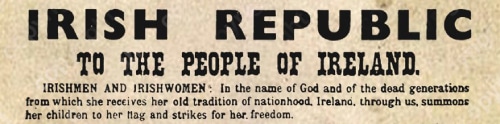

In the wake of Brexit, talk of constitutional change in Ireland has gathered attention and momentum. One question that occasionally surfaces in these conversations is whether Ireland should join the Commonwealth.

The suggestion often comes from a place of goodwill — the idea that joining might serve as a conciliatory gesture to Unionists, signaling a spirit of inclusion in any new all-island arrangement. Constitutional change would be a political paradigm shift. Northern Ireland would be leaving the United Kingdom to join a United Ireland, and Northern Ireland would also be leaving the UK and joining the EU. In such transformational circumstances it may not be unreasonable for Ireland to concurrently join the Commonwealth in an effort to ease Unionist concerns. Imagine if Northern Ireland was to leave the UK but shortly thereafter Ireland joins the Commonwealth in a spirit of generosity & reconciliation. Quid pro quo. In a well managed & sequenced process this could potentially carry a positive political and social impact in Northern Ireland.

While the sentiment is laudable, the idea itself may not be deliverable, or necessary.

The Limits of What’s Politically Feasible

Irish nationalism should, without doubt, address Unionist concerns with generosity. But there are boundaries to what can realistically be delivered.

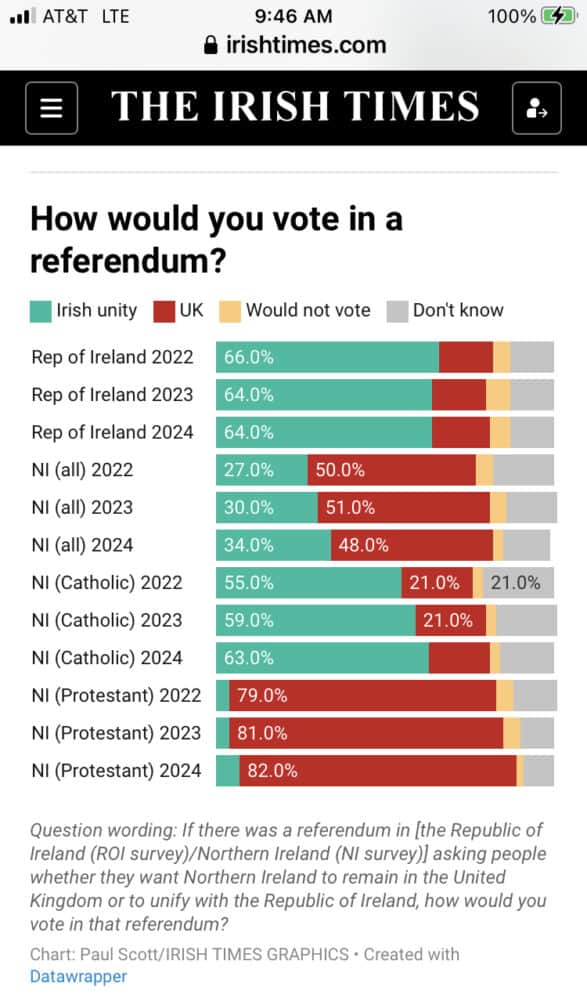

Research and polling has shown that issues such as changing the Irish flag or national anthem would be politically difficult and risks splitting the nationalist base. Joining the Commonwealth could fall into the same category — a step too far for many, carrying more symbolic risk than practical reward.

What Unionists Actually Want

Interestingly, research also indicates that Unionists themselves are not calling for Ireland to join the Commonwealth. The ARINS Project found that what matters most to Unionists in any future constitutional arrangement is the ability to retain British citizenship and access to the NHS.

Joining the Commonwealth, by contrast, offers little tangible benefit to Unionists and harbours potential pitfalls for Nationalists. It may even distract from the issues that really matter to all those most directly affected by unification.

The Good Friday Agreement Provides a Framework

The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) already provides clear guidance on citizenship. It allows those born in Northern Ireland to be British, Irish, or both, and to hold corresponding passports.

Here I must be clear, be in no doubt, that provision of the GFA will endure after unification. Those who choose to do so, will retain their “British-Only” identity & their British citizenship — and thus their connection to the Commonwealth — regardless of Ireland’s Commonwealth status or future Unitary status.

In practical terms, Unionists are part of the Commonwealth before, during, and after unification. By virtue of their British citizenship they never left the Commonwealth, even if Ireland is united. Membership of the Commonwealth is based on citizenship, not country of residence. Consequently, there is no need for Ireland, as a Nation, to consider joining the Commonwealth. This reality around citizenship should be recognized and codified in both Irish and British law. The British–Irish Intergovernmental Conference would be the appropriate forum to formalize such an understanding.

The Risk of Division Within Nationalism

For Irish nationalism, the question of joining the Commonwealth carries significant internal risk. It could divide nationalist voters, parties, and organisations at precisely the moment when unity of purpose is essential.

Moreover, nationalists must remain alert to the possibility that some symbolic “asks” from Unionism — such as changes to flags, anthems, or Commonwealth membership — could be merely political tactics designed to slow the process or fracture the pro-unity base.

A pragmatic approach – perhaps using the “Devolution Model” during a transitional phase – to manage sensitive identity issues, may provide a steadier path toward full integration.

A Better Way Forward

Given the limited demand from Unionism and the potential for nationalist division, there is no pressing need for Ireland to pursue Commonwealth membership.

A more constructive approach would be for the Irish government to amend the Constitution to guarantee that those born in Northern Ireland who identify as British can retain that citizenship permanently — an entitlement passed down to their children and grandchildren.

Such an amendment would:

-

Reflect the obligations and spirit of the Good Friday Agreement

-

Protect political equality for all citizens in a unified Ireland

-

Prevent the disenfranchisement of Northern “British-only” citizens from Presidential elections and referendums

-

Offer genuine reassurance to the Unionist community without Ireland formally rejoining the Commonwealth.

- Avoid the threat of division within the Nationalist base, at the moment when unity of purpose is essential.

Ireland should extend support to British citizens resident in a unitary state who wish to participate in Commonwealth activities, such as the Commonwealth Games. No formal membership is required from Ireland, but respect for the British identity of the participating athletes who reside in a Ireland is clearly deliverable. The answer to the question lies in recognition, respect & support at the individual citizen level, rather than elevating the issue to a National level.

Symbolism Isn’t Substance

Joining the Commonwealth might appear, on the surface, to be an act of reconciliation. But reconciliation built on symbolic gestures rather than legal guarantees risks being shallow and short-lived – temporary and tokenistic.

A confident, inclusive Ireland can achieve much more by entrenching citizenship rights in Bunreacht na hÉireann (the Irish Constitution) rather than by revisiting colonial-era affiliations. For example, under the current provisions of Bunreacht na hÉireann only Irish citizens can vote for the office of President and in Referendums. This means, in a Unitary state “British-only” citizens from the North would not able to vote even if they wanted to. We cannot repeat the mistakes of the past, as historically evidenced in Northern Ireland, where some citizens were systematically excluded from the electoral process. Guaranteed equal treatment under the Constitution is substance, membership of the commonwealth is symbolism.

Conclusion

Ireland does not need to rejoin the British Commonwealth to build a shared future. The political risks of dividing the nationalist base far outweigh the symbolic benefits.

Instead, the path forward lies in constitutional generosity — recognising and protecting the rights of all citizens on the island, British and Irish alike.

That would represent not just compliance with the Good Friday Agreement, but a mature, forward-looking nationalism capable of embracing diversity without compromising sovereignty.

In short: A united Ireland can be a warm house for Unionists — without rejoining the Commonwealth.

Charles Lord was born in Belfast. He completed his BA in Business while at University in England. .He has spent most of the last 38 years in the U.S. where he currently resides. Charles has a background in both business and education, he also holds a Masters Degree in Education. In addition to owning and operating the CelticClothing.com he taught Web Design and Digital Marketing in the western suburbs of Philadelphia where he was Department Chair of the Business Faculty for 20 years. He follows football (soccer). He is not a member of any political parties.