In 1847 the Native Americans of the Choctaw nation took up a collection.

Moved by news of starvation in Ireland, a group of Choctaws gathered in Scullyville, Oklahoma to raise a relief fund. Despite their meager resources, they collected $170 and forwarded it to a U.S. famine relief organization. It was both the most unlikely and the most generous contribution to the effort to relieve Ireland’s suffering.

Begun two years before in the fall of 1845, the potato blight and subsequent famine had reached its height in 1847. It was, of course, much more than a mere natural disaster.

British colonial policies before and during the crisis exacerbated the effects of the potato blight, leading to mass death by starvation and disease. For example, in March of 1847, at the time of the Choctaw donation, 734,000 starving Irish people were forced to labor in public works projects in order to receive food. Little wonder that survivors referred to the year as “Black ’47.”

First through letters and newspaper accounts, and later from the refugees themselves, the Irish in America learned of the unfolding horror. Countless individuals sent money and ship tickets to assist friends and family. Others formed relief committees to solicit donations from the general public. Contributions came from every manner of organization, from charitable societies and businesses to churches and synagogues. By the time the famine had ended in the early 1850s, millions in cash and goods had been sent to Ireland.

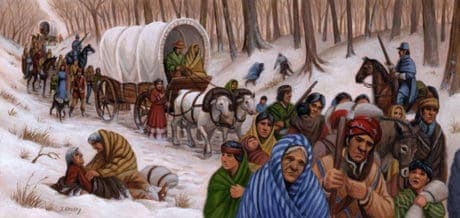

What made the Choctaw donation so extraordinary was the tribe’s recent history. Only 16 years before, President Andrew Jackson (whose parents emigrated from Antrim) seized the fertile lands of the so-called five civilized tribes (Chickasaw, Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, and Choctaw) and forced them to undertake a harrowing 500-mile trek to Oklahoma known as the Trail of Tears. Of the 21,000 Choctaws who started the journey, more than half perished from exposure, malnutrition, and disease. This despite the fact that during the War of 1812 the Choctaws had been allies of then General Jackson in his campaign against the British in New Orleans.

Perhaps their sympathy stemmed from their recognition of the similarities between the experiences of the Irish and Choctaw. Certainly contemporary Choctaw see it that way. They note that both groups were victims of conquest that led to loss of property, forced migration and exile, mass starvation, and cultural suppression (most notably language).

Increased attention to the Great Famine in recent years has led to renewed recognition of the Choctaw donation. In 1990 a delegation of Choctaw officials was invited to participate in an annual walk in County Mayo commemorating a tragic starvation march that occurred during the Famine. In honor of the special guests, the organizers (Action From Ireland, or AFRI) named the march The Trail of Tears. Two years later, two dozen people from Ireland came to the U.S. and retraced the 500-mile Trail of Tears from Oklahoma to Mississippi. That same year the Choctaw tribe made Ireland’s President Mary Robinson an honorary chief.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of these events is that while they commemorate dark chapters of the past, they are focused on the present and future. In other words, they seek to dramatize the need to stop starvation and suffering worldwide. As the plaque on Dublin’s Mansion House which honors the Choctaw contribution reads: “Their humanity calls us to remember the millions of human beings throughout our world today who die of hunger and hunger-related illness in a world of plenty.

— This article was contributed by Dr. Edward T O’Donnell.

2 thoughts on “The Great Hunger — The Choctaw Send Aid”

Here it is- another humbling lesson in history.

I’m Irish- American and have always been drawn to the Indigenous Peoples of the USA and Canada.

I was fully aware of the shameful Trail of Tears. But I never knew of the Choctaw’s incredible humanity, compassion, and generosity during the Great Famine.

I am most grateful to have read this. I have no doubts my ancestors were touched by these acts of love.

I live in a town in southeast Maryland that was colonized early in the 17th century. At that time, in the nearby port of Oxford, the British colonial authority allowed trade in goods and people. There is a surviving signpost from the era that lists the price, in bales of tobacco (coins of the Crown could not be exchanged), for imported goods, including furniture, housewares, clothing, Irish Indentured Servants and African Slaves.

A few miles away, in what is now Vienna, MD, the British Crown created a Native American reservation for the local tribes who had assisted and traded with early settlers. The reservation was closed in the late 18th century, but many indigenous people still live in the area, along with descendants of Irish Provinces, and descendants of African Villages, and we celebrate and honor each others cultures twice a year on the grounds of the former reservation at a place called Handsell House. All are welcome here.